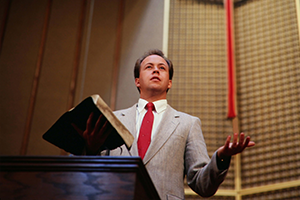

SERMON: FAITH OF A FATHER

by Gordon MacDonald

from Preaching Today Tape #45

Ironically, Eli was a rotten father. The first two shots he took at raising

boys were an abysmal failure, and he gave the world two monsters. So God must

be a gracious God, because he gave Eli a third chance. When Hannah and

Elkanah presented their precious young son for service at the temple, this

time Eli performed.

Eli, what is your job description in the raising of Samuel? Answer: My

mission is to so raise this young man that when the voice of God is heard, he

will know how to decode the noise and respond obediently to it. There could

be no higher call for the man who was privileged to be called father.

Any healthy male past the age of puberty can become a father, but it takes a

man who understands this mission to be a father. The mission of the man

called father is to raise children in such a way that, like Samuel, they may

be able to decode the voice of God and make a proper choice as to whether or

not they shall respond. This encounter happened in the tabernacle at Shiloh,

for God called people to himself in special places.

In Lexington, Massachusetts, where Gail and I and our children, Mark and

Kristi, lived for thirteen years, we lived on Grant Street in a small,

ranch-type house with six or seven rooms and one bathroom. I now shake my

head in consternation to realize I raised a family with one john. One year

ago, my wife and I said good-by to Grant Street. As we got into the car, I

said, “Why don’t we go back into the house one more time. Let’s tour each

room and see if we can form one final memory of something that happened in

the vocation of mothering and fathering during those thirteen years.

The first room is the breeze way, sometimes the family room. It was a

marvelous place to eat and have a lot of fun in as a family. I remember

coming home one day when our children were probably around the ages of nine

and six. As I entered the breeze way, the two of them were standing

nose-to-nose, ripping each other apart. I was amazed at the words and the

anger. I was grieved, as a father would be watching his children rip each

other apart. Then I put my hands on their shoulders so they maintained this

limited distance, and I said, “Listen carefully. This place is called home.

It is unlike any other place. When you enter a home, people do things

differently. In a home, they build each other. Did you hear that word? They

build each other. Say it for me, very slowly.” And both children said, “Build

each other.” “Say it again louder, so I can hear you better.” “Build each

other.” “Yes, that’s what you do in a home. You build each other. Outside

that door, people carve each other up. They compete with each other. And

sometimes you have to look over your shoulder to see who may be coming up

behind you. You should never have to do that in a home. I anticipate from

this moment forward that the content of your conversation will always be in

the mode of building, because here we are growing human beings to the glory

of God.” That’s a definition of a home: a place where people are built. The

rest of the world is a place where people are discriminated against, are

denied their rights, are made to feel something less than they are. But in a

home, the number-one task of parents is to build people, to create an

environment in which people can grow.

I stood one day at the edge of a newly planted lawn. I loved the cleverness

of the planter who had put a sign there that said, “Please do not walk on

this ground; seeds are at work.” A sign like that could go on the front of

every home. Seeds are at work. Children are being grown. People are being

built.

Our cliche became build. It came home to roost one day when I said an idle

word to my wife and one of our children said to me, “Now Dad, was that a

building statement? Why don’t you say it again to Mom and see if the second

time you can do it right.”

I believe one day those men entrusted with wives and children will stand

before God, and among the first questions he might ask would be, “Did your

child and spouse grow to be all that I designed them to be in the environment

you created?” In the breeze way, the great memory was the admonition to

build.

You go from the breeze way to the kitchen. At one end was a lovely old table

we had refinished, and around that table we ate our meals. When it was time

to eat, the phone came off the hook because for the hour we were at the

table, the family was the ultimate priority. That did not happen by accident,

for as our children began to enter the pre-teen years, Gail and I discovered

that our family schedule was falling into the hands of everybody outside the

house. The children were victimized in a positive sense by the wonderful

things to do in the school. The church had its own programs. The community

had its programs. If we did not have control of our family calendar, before

long we would be going in four different directions, having almost no useful

time together.

One day my wife made an announcement with my support. She said, “From this

day forward, every evening at supper time, we are going to eat together. It

is an inviolable part of the daily schedule. I don’t care what time we eat,

as long as you tell me when you call can be here.” My contribution was to

suggest that supper time is more than eating. It is a relational event in

which people talk. That, I believe, is the second mark of a home in which

people grow: people learn to talk with each other. No one will learn to talk

if the time is not taken and if interruptions are not minimized. As we stood

in the kitchen of the empty house, we began to think of all the great

conversations that happened around that old table: The evenings when one of

the children came home defeated in an event at school and the opportunities

to give vent to feelings and frustrations; the moments when the interesting

questions merged into long conversations about sex, about marriage, or how

you hear the voice of God.

If your children are anything like mine, they don’t like to talk. “How was

your day?” “Good.” “Is that all, good?” “Yeah.” “But, that’s the way it was

yesterday, and the day before that.” So fathers have to be creative, like,

“If you don’t tell me what was the most interesting part of your day, it will

cost you a quarter.” Sometimes it takes a father who admits to his children

that he also had struggles that day, or that he has failed. But sooner or

later, because the time is taken, families learn to talk.

When you leave the kitchen, you come to the living room Our living room had a

large, plate glass window, and my memory as I entered that room was of our

daughter, Kristi, who often sat on the love seat looking out the window. I

often saw her there at 5:30 in the morning, when, for an hour with her Bible

and journal, she would spend time ordering her world and bringing it into

reconciliation with God.

She often did her homework out there. And it was not unusual to walk into the

living room and see eight or ten young people sitting around the fireplace as

she and the others talked about the Scriptures or a summer mission trip. The

living room was a lovely place, and Kristi liked it very much. But one

Saturday afternoon, Kristi sat in front of that window, and I knew the

thoughts this time were difficult thoughts. Gail had put me on to the fact

that Kristi was struggling, and maybe it was time for her father to enter the

act. The issue was simple. She had to make a big decision as to where she was

going to attend high school. One group of friends thought she ought to go to

the public school, and the other group thought she ought to go to the

Christian school. She knew that to make a decision would hurt one group. Here

was a fourteen-year-old child, more girl than woman, wrestling with a massive

decision.

As I listened to her talk, I finally heard myself saying, “Kristi, all men

and women, be they teenagers or adults, have moments when they are like an

oak tree or a tulip. The trick is to know which you are. Oak trees grow and

stand tall. They take a long time, but when they get to full growth, no one

messes with them. You walk around them, because oak trees stand by

themselves. They are strong and beautiful and tall. And Kristi, I have seen

you when you are an oak tree. On the other hand, tulips grow to fullness and

beauty also, but even at their greatest height and beauty, they need to be

protected. You need to build a fence around a tulip, but you don’t have to

worry about an oak tree at all. So, it’s important for fathers to ask their

daughters, `Are you today an oak tree or a tulip?’ because if you are an oak

tree, Kris, I’ll leave you alone. But if you are a tulip, I’ll build a fence

around you today.”

She pondered the alternatives, and then came the tears and finally the quiet

voice. “Daddy, today I’m a tulip.” With those code words, father knows it’s

time to protect. Thank God, there are moments when fathers have that

opportunity to build a fence. And thank God for the moment when he gives us

the spirit of discernment to know when our children need the fence because

they are tulips and when we need to stand aside because they are becoming oak

trees.

If you walk down the hall, there’s a bedroom where our son, Mark, lived. I

remember that bedroom vividly. And now a memory quickly came to me. Mark was

a sixth grader when the event happened. He had rushed in the door of our home

after school and said, “The kids have asked me to go with them to Cape Cod

this weekend. There are fourteen of us going, seven boys and seven girls.

It’s going to be fantastic!” Sixth grade. For seventy-two hours. I took one

look at him and with all my good interventive techniques, said “No way!”

Sixth grade is generally the year when boys and girls form peer groups, when

popularity becomes an issue, when being in the in- group is the most

important thing in the world. To be invited to go to the Cape for a weekend

is a special privilege, and to hear from your parents that there’s “no way”

is devastating.

Mark quickly disappeared, and for a half hour I didn’t hear anything from

him. I began to search the house, but I couldn’t find him. Then suddenly my

mind turned back to the bedroom, and I realized there was something unusual

about that bedroom: the closet door had been shut. So I went back into the

bedroom and opened the closet door. There, back in the corner, was my son,

sitting with his knees wrapped up to his chest, quietly weeping. I’d never

seen him do that before.

There aren’t textbooks that tell a father how to perform in a moment like

that, but instinct told me I ought to join him. I found myself closing the

closet door behind me and getting down on the floor in that darkened closet.

I sat in the darkness for ten minutes and listened to my little boy weep.

Finally, when there were no more tears, I began to rethink the decision I had

made and whether I had been too arbitrary. “Son,” I said, “let’s talk. It’s

obviously very important to you. Tell me about the ground rules. Tell me

what’s going to happen.” And with that, the story came out, the story I had

been too gruff to listen to. When he finished, I said, “Bud, I’ll back off.

YOu go. But I want you to promise you will watch everything that happens this

weekend. Watch the way the young people interface with each other. Promise

that the minute you get back, the two of us will sit down and have a long

talk about everything you saw and how you felt about it.”

He said, “Dad, I promise.” He went, and thank God, he had a thoroughly

miserable time. “It was crazy, Dad. Those parents didn’t care what their kids

did. The kids were left on their own, hour after hour. Something wrong could

have gone on. You and Mom would have never acted that way. I’m really pleased

that you let me experience that, because I saw how different families treat

each other.” From that weekend, because I made a choice to flex as a father,

my son and I had a different relationship, which lasts until this day. He

learned and I learned that part of good fathering is to have principles and

convictions but also to learn how to negotiate and flex and allow one’s son

or daughter to take a few chances for the possibility of learning valuable

lessons on their own.

Down the hall is the bedroom where Gail and I lived. When we reached that

room, we laughed a bit as we remembered that it was to that room late in the

hours of the night that the children often came with all sorts of wonderful

and troubling stories. There was the night at 12:30 when a soft knock came on

the door and a rather quiet male voice said, “Dad, I don’t know how you are

going to take this, but I got a speeding ticket tonight. You warned me, and

I’ve gotten it and I’m very, very sorry.” And he sits on the edge of the bed

and he talks about how he made the mistake. You say to yourself, “Thank God

we have achieved a point where the boy can admit he’s wrong.” We talk about

what we’re going to do about it. We give each other an embrace, and he goes

to his bed.

Or there was the night when the same kind of knock came on the door, and this

little it’s a feminine voice: “Daddy? Mom? Can I come in?” And a little now

turned seventeen sits on the edge of the bed and tells you about a handsome

guy she has met, and how he has feelings for her, and she has feelings for

him. You look mesmerized as the little girl unfolds the fact that now she has

become a woman, her heart has been captured. Just two weeks ago I walked her

down the aisle to commit her to that young man. But there in that bedroom, we

heard the story of a budding romance for the first time.

Gail and I look at each other in that empty bedroom and remember moments like

that when there was the admission of pain and the first seeds of joy, and we

say to ourselves, “Thank God, our children knew this was a room to which they

could come no matter what the hour to talk about what was in their hearts.”

The garage brought to us the memory of a red pickup truck that for many years

was housed in it. When our son turned sixteen, the learner’s permit was

hardly dry or in his billfold when he came to me and said, “Dad, next Friday

I have a date. I’d like to take her in the truck.” I said, “Well, Bud, you

can’t do that. You only have a learner’s permit, and you can’t go out at

night without someone who has a license.” “Dad, she’s eighteen and a half.”

“Where is the date?” “Boston.” “What time does it start?” “Five-thirty.”

“Have you ever driven in Boston at 5:30 on Friday afternoon?”

I wanted to say, “No way!” but I had learned my lesson. I said, “Bud, give me

two hours to think about it.” I go call the father of the girl and say, “Don,

you know your daughter and my son have a date next Friday, don’t you?” He

said, “Yes, I do.” “How would you fell if you knew that Mark was going to

drive on that date with just a learner’s permit because your daughter has a

driver’s license?” He said, “Gordon, I trust Mark’s judgment. If you feel he

should do that, it’s fine with me.” The two hours are almost gone, and I say,

“Mark, my answer is yes under one condition. ON the night before your date,

you and I will drive the route to the date at the same time of day, and you

will permit me to create any kind of circumstance and you will have to react

to it.” He said, “Sure, Dad.” So the next Thursday at 5:30, we started out in

rush-hour traffic, bumper to bumper. I suddenly say to him, “Son, I’m sorry,

but your right front tire just blew out.” “What do you want me to do?” “What

do you do with tires that have just blown out?” “You change them.: “Then get

over there and change it!” So we pull over into the breakdown lane with me

praying that a copy won’t stop, and I’ll have to explain all this. Mark

climbs under the pickup truck to get the jack. Jacks in most pickup trucks

are under the hood. Mark found out that afternoon. He also discovered what to

do when an alternator burns out. He discovered what you have to do when you

plan to go down an exit ramp and the freeway is blocked because of

construction, and you have to take an alternate route. He also learned what

happens if the truck completely breaks down and you have to make a decision

late at night whether to call the girl’s father or not. When we got home that

night, I think Mark knew every contingency about driving a pickup truck to

Boston on a Friday afternoon. I smile about that as I stand in the empty

garage in the house on Grant Street. But that’s the act of fathering. It’s

releasing the child to face the possibilities and to grow through experience

once you have taught him everything that’s possible to give him.

The last room we walked through was the dining room, and the memory I have of

the dining room is not as happy as all the others. It came the night of a

birthday party for me. Gail had cooked my favorite food. She put together a

beautiful cake. The presents were all wrapped. The lights were now low, and

the family gathered for the supper. But it was clear from the outset that the

children were not in sync with the evening’s activities. They were caught up

too much in their own thoughts. Soon they got to complaining about a

vegetable they didn’t like (which I did), and they started bickering with

each other. Then they sprang up from the table and announced they were going

to watch a favorite television show and they’d appreciate it if we wait for

the. We sat at the table for thirty minutes, me saddened that the kids had

forgotten it was my birthday, that they were spending too much time thinking

about things that were important to them. We were even tempted to ask the

questions parents ask on occasion, “Where did we go wrong?”

Finally after an hour they came up and one said, “Where’s the cake? When are

we going to open the presents?” I said, “I’m sorry, the party has been

canceled.” “It can’t be canceled. This is your birthday.” I said, “I know

it’s on the calendar, but a party is a party only when the people determine

it’s supposed to be a party and act in a party mood. Two of the four of us

decided today to party by themselves. So maybe we’ll have the party in

another few nights. But not tonight. The party’s over.”

It was not a pleasant scene as our children walked away with tears. Later

that night, sitting at the edge of the bed with my son and listening to him

apologize to God and to his father because of his selfishness, I realized

there are moments in the raising of a family when fathers have to make

difficult decisions and say and do painful things. In my journal that night,

I wrote these words: “It would be so easy, God, to make simple decisions

dictated by convenience and the desire to be liked. But just as I withdraw

the hand that offers pain to my children, you remind me, God, that one never

learns and grows and blooms when the climate is easy. Teach me therefore,

God, like a father to think with eyes and ears, to brood with a heart just

like yours, which sees in the scope of eternity’s process what makes people,

even my children, become like your Son, Christ. The ecstasy of this one

moment when simple decisions might bring temporary tranquility is not to be

compared with the maturity of all the tomorrows through which my children

must live.”

For the final time, we locked the door on the house on Grant Street. It’s not

quite the same place with the furniture gone and the curtains down and the

pictures off the wall and the shouts and the joys and even the tears of the

children not there any longer. It’s just an empty, four-walled structure that

a new family will fill with its artifacts in another day or two. A house is

not made of dry wall, studding, and plate glass windows. No, a house is a

place that becomes a home when there is a decision on the part of a father

and a mother to make the people inside it grow. And there comes a day when,

having grown, the children leave and become what their choices are making

them become. As we drive up Grant Street, leaving behind us the empty house,

we are able to pray, thanking God that he gave us a home where children grew.

For some of you, that is a dream yet to happen. For others, it’s a dream in

progress. For many of you, like me, it is a past memory. But thank God for

fathers who help children and young people hear the voice of God. It is one

of the greatest privileges in the world.

Copyright 1995 (c) Christianity Today, Inc./LEADERSHIP JOURNAL

PTSscPT45a5616